let code die

just want to quickly connect a few thoughts here, inspired by Mike Cook posting this:

"Let Code Die" is a cool mantra I've come across this week that I think a lot of game developers and academics would vibe with. It has an interesting contrast with/against archival work; it embraces the idea that you can sort of 'dehydrate' the past to recover later. www.pastagang.cc/blog/let-cod...

— Mike Cook (@mtrc.bsky.social) 2025-01-31T11:55:05.824Z

this links to the pastagang blog and a post almost certainly mainly or exclusively written by Lu [not true! see correction below]. pastagang is a bunch of people who make music together by writing code in a shared room (this one: http://nudel.cc/ - you can go make music there right now! you can join the pastagang!)

that post talks about a lot of futures of computing, talking about three different approaches to it, and trying to find the common element:

my idea was that they all acknowledge that code can break and die in various ways, and that we should plan around that.

in my opinion, the three movements don’t say that code death is something to be avoided, but rather that it is something to be handled gracefully.

something here about entropy, about failure and accepting it, using it, turning it into something else.

and then Mike connects this with the idea of the archive as attempting to not just capture the artefacts that resulted from people's lives, but, more importantly, to try to understand the context that people made them within. the kind of archival work that Holly Neilsen partakes in:

When I’ve had people ask how I locate play and how they can emulate it, I can say “start by reading around 38,500 pages of people talking about all different aspects of their lives and no doing keyword searches doesn’t work”

— Holly Nielsen (@hollynielsen.bsky.social) 2025-01-17T11:47:16.531Z

or look at the work of Kat Brewster, looking through the archives of the GayCom BBS, which was operated for and by gay men during the AIDS crisis:

Kohn’s work establishing GayCom as a means for LGBTQ+ people to connect during a “time of multiple crises,” was integral to his ethos of liveware — an approach that valued the people who maintained systems just as much as their hardware or software.

this kind of archival work is kind of defined by it's futility - no matter how extensive the archive, it will never fully capture the richness and texture of life. but it can get close! and it can give us glimpses of lives outside our own.

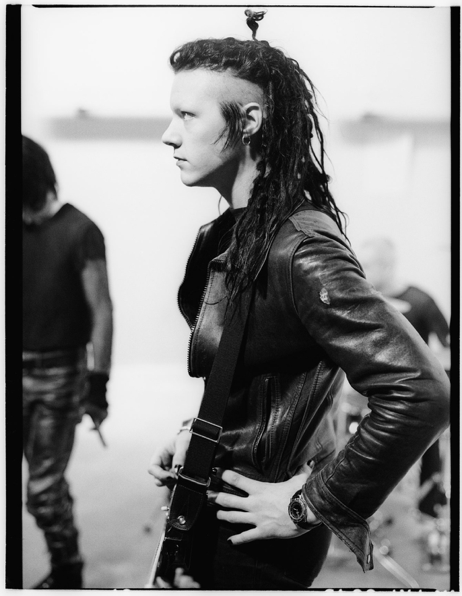

but actually i think the thing that i thought of when i saw "let code die" is that it's a mantra that has come about [is here used] in a very specific context, which is people playing music together. and that instead makes me think of this long article on Nine Inch Nails, mysticism and Robin Finck that i read instead of getting out of bed this morning.

here's a relevant section:

It has long been said by musicians that you can tell a good one by what he doesn’t play, by the notes he chooses to leave out. It reveals his understanding of the song as a structure, and how his decisions not only hold it up but give it space to breathe, let it live its own life without him. It also shows how self-confident he is as a player, knowing that he doesn’t have to blow his load over everything to leave a mark. Of all the rock gods, Robin is the only one I can think of who lets one or two notes do for him what the rest of the guys use dozens for.

Look at the video of GNR guitarist Richard Fortus and Robin playing an instrumental cover of Christina Aguilera’s ‘Beautiful’. Fortus starts with a cascade of noodling. He’s a fine player, and I have nothing against him, but when Robin starts playing, you can see what is soul, and what is not. It has to do with Robin’s timing, his choices about what not to play. Remember that he thinks of the breaths between phrases, like a horn player, so he doesn’t fill all the space with wiggly notes, showing off how quickly he can go through scales. He lets one note sing, really sing, and there are as many soundless pauses as there are notes. At around two minutes, he starts to play rhythm so Fortus can have his turn to solo. Listen to the difference. The spacing becomes rapid and crowded, which indicates rock-guitar expertise, and draws the focus to Fortus as a player, but pulls the focus away from the song. It’s like Fortus has something to prove about himself that doesn’t include the song, whereas Robin is content to let the song be bigger than he is, which it is.

i feel like at this point in the post i should draw a connection between these multiple perspectives. but i don't know that i have anything neat and conclusive to say. the value of leaving space. the value of accepting failure. glorying in the moment, knowing that it's fleeting. making connection with others. all of these things.

couple corrections:

- the post was not by me. from a count, at least nine people participated. i just moved some of it to a separate file. this is why its best to say "by #pastagang". because it gets so hard to keep track, and its best not to give credit to the wrong person, while discarding the efforts of the others

- the mantra didnt come about in this specific context. its from the tadi web, which nudel is part of, and @froos@post.lurk.org is running with. see: https://garten.salat.dev/meta/youre-do

i regret the inaccuracy, and i especially regret erasing the work of a diversity of contributors while making a post trying to connect a variety of ideas together

Member discussion